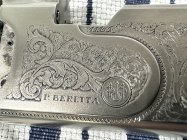

I’ve seen some fantastic posts on these forums of incredible gunstock work. I can only dream of being that capable working with wood. I know I’d be useless at it. Despite the use of some wonderfully figured wood there seems in large part a tendency to spray a varnish finish or if oil is used, to not take it to its fullest potential. Personally, I have always preferred the finish I see on fine guns done in the “best London oil finish” be they shotguns or rifles. Most of these produce a gun with a mirrorlike finish on the wood and with maximum contrast in the figuring. And so, I thought I’d create a thread which shows the process I am using to redo the finish on my Beretta shotgun.

This isn’t a ‘fine’ shotgun by any means. It’s a Silver Pigeon S which I purchased back in 2006. It’s had many years of solid use in the field driven-bird shooting and shooting simulated-bird clays. At one point, it had a rubber cheek rise ‘fitted’ by the chief instructor at Holland and Holland shooting grounds just outside of London. I say ‘fitted’ but it was attached simply with electrical tape! The gun had suffered a number of dents over the years, including some from being hit by pieces of a clay shot by a friend while I stood well behind – on the very first day I used the gun!

Nonetheless, I felt the wood perhaps showed more promise than its production finish (and use) allowed. (Beretta have no doubt reduced the quality of their base model guns since I purchased mine.) And so, I decided to embark on the process of stripping off the previous finish, fixing any dents and scratches, and trying to bring the best out of the wood with a traditional oil finish.

A lot of what I’m doing is summarized excellently in a video made by the folks at James Purdey and Sons and posted on their Instagram account. The video series is well worth watching and the stock finishing part begins at about the 1 hour 20-minute mark in the one linked to below. I should say from the outset that I’m not at all a professional at this stuff. I’m very much an amateur following the processes outlined in that video and tutorials provided elsewhere. Prior to this stock I did another a couple of years ago although not to the same level of quality. For this project, I had to relearn some of what I had done before and learn a few new things this time, largely from trial and error. Were I to do another stock, I think I’d be much more efficient than this time.

https://www.instagram.com/tv/CIoPydLnsWk/?igshid=MTc4MmM1YmI2Ng==

I should also say that this isn’t a process for those seeking instant gratification and quick results. The fellow from Purdey noted in their video that they make a minimum of 40 applications and up to 50 depending on the grain of the wood. And they’re using the best quality wood available. Mine is far from that with likely more marked grain, at least in places. They also have the benefit of considerable experience. (Their apprenticeship takes 5 years.) This is a process that requires time and patience. Expect to be doing a little of this for one to two months depending on your commitment. At most, you will do two applications per day else later applications simply undo prior ones which haven’t had time to cure sufficiently.

Wood Preparation

The first step was to remove the butt pad, action and fore-end metal work and strip the old finish off. I used MinWax Antique Furniture Refinisher, some 0000-steel wool and a new toothbrush for the checkering.

To be honest I was a little disappointed with the stripped wood. It was still quite dark and didn’t have the extent of figuring that I’d hoped for. (Maybe it had been soaked in stain at the factory and perhaps there would have been a better finish stripper to use.) Even so, it was clear that there was enough there for the end-product to be substantially better than before.

Next came raising the dents. I made up a solution of Oxalic acid (using the mix ratio recommended for wood) which was used for this and during papering (see below), dipped a rag into the solution and, laying it down over the affected area, brought a hot iron to bear over the dent being careful to not singe the wood. The dents rose quickly to the level of the rest of the stock. (Don’t breathe the fumes of the evaporating vapors!)

Next came papering (sanding) the stock. In hindsight, I might have paid greater attention to how the head of the stock fitted the metalwork of the action. Beretta doesn’t do an aesthetically good job of this on their cheaper guns with the head largely over-sized for the action by several millimeters in places. It would have been a good opportunity to tidy this up. However, I didn’t notice beforehand and, since I had the metalwork off while sanding, I didn’t notice it until the metalwork was refitted prior to starting the finishing process.

Papering was the simple process starting at 180 grit and moving up through paper grades all the way to 2000 grit. (Actually, I did a light sand at 2500 grit, but I think this isn’t needed given all that follows.) All sanding was done dry even though wet ‘n dry paper was used. Between grades of paper, I ‘raised the grain’ by dampening the stock (excluding the checkering!) with the oxalic acid solution and then immediately drying it off with a heat gun. (See the Purdey video for a demonstration of this process.) The more we can lift the grain by doing this the smoother the wood will be once sanding is finished. The most tedious part of this entire process is filling in the remaining grain with finish and so the more we can do to make that easier the better. If you don’t want to use oxalic acid for this process (or raising dents) a solution of 75% ethanol alcohol/25% water will work.

Here’s a pic of what the wood looked like once papering was completed:

You must be absolutely meticulous throughout this preparation phase. Imperfections will come to haunt you later. Ask me how I know… Clean off the wood and give it a very close inspection. If there are spots or areas that you think can benefit from additional grain raising deal with them now. Here’s a couple of examples that should have been better dealt with early on. 40+ slacum applications later and they were still issues. I thought I had properly raised the dent at the top but a chip of damaged wood came out during sanding. The bit on the right looked deceptively innocent. Even more deceptive was the grain on the other side of the stock. Unfortunately I didn't photograph that.

The final part of this stage is to burnish the wood with a small amount of ‘red oil’ (more on this shortly) and a chamois.

Grain Filler

I don’t use a specific grain filler that would be sanded once dry. Instead, I use rottenstone combined with slacum to create a sort of dark cement in the grain. (See below.) This provides great local contrast. There exist, however, products that you can use at this stage – particularly if your wood has very open grain. I resisted the temptation to “cheat” but if you can’t fix difficult areas via raising and sanding then perhaps a grain filler has merit (particularly I troublesome areas). A grain filler will save a lot of work later but you may not get the ‘micro contrast’ of a grain that’s been filled with rottenstone and slacum.

Trade Secret (see below) make a grain filler intended for this process.

This isn’t a ‘fine’ shotgun by any means. It’s a Silver Pigeon S which I purchased back in 2006. It’s had many years of solid use in the field driven-bird shooting and shooting simulated-bird clays. At one point, it had a rubber cheek rise ‘fitted’ by the chief instructor at Holland and Holland shooting grounds just outside of London. I say ‘fitted’ but it was attached simply with electrical tape! The gun had suffered a number of dents over the years, including some from being hit by pieces of a clay shot by a friend while I stood well behind – on the very first day I used the gun!

Nonetheless, I felt the wood perhaps showed more promise than its production finish (and use) allowed. (Beretta have no doubt reduced the quality of their base model guns since I purchased mine.) And so, I decided to embark on the process of stripping off the previous finish, fixing any dents and scratches, and trying to bring the best out of the wood with a traditional oil finish.

A lot of what I’m doing is summarized excellently in a video made by the folks at James Purdey and Sons and posted on their Instagram account. The video series is well worth watching and the stock finishing part begins at about the 1 hour 20-minute mark in the one linked to below. I should say from the outset that I’m not at all a professional at this stuff. I’m very much an amateur following the processes outlined in that video and tutorials provided elsewhere. Prior to this stock I did another a couple of years ago although not to the same level of quality. For this project, I had to relearn some of what I had done before and learn a few new things this time, largely from trial and error. Were I to do another stock, I think I’d be much more efficient than this time.

https://www.instagram.com/tv/CIoPydLnsWk/?igshid=MTc4MmM1YmI2Ng==

I should also say that this isn’t a process for those seeking instant gratification and quick results. The fellow from Purdey noted in their video that they make a minimum of 40 applications and up to 50 depending on the grain of the wood. And they’re using the best quality wood available. Mine is far from that with likely more marked grain, at least in places. They also have the benefit of considerable experience. (Their apprenticeship takes 5 years.) This is a process that requires time and patience. Expect to be doing a little of this for one to two months depending on your commitment. At most, you will do two applications per day else later applications simply undo prior ones which haven’t had time to cure sufficiently.

Wood Preparation

The first step was to remove the butt pad, action and fore-end metal work and strip the old finish off. I used MinWax Antique Furniture Refinisher, some 0000-steel wool and a new toothbrush for the checkering.

To be honest I was a little disappointed with the stripped wood. It was still quite dark and didn’t have the extent of figuring that I’d hoped for. (Maybe it had been soaked in stain at the factory and perhaps there would have been a better finish stripper to use.) Even so, it was clear that there was enough there for the end-product to be substantially better than before.

Next came raising the dents. I made up a solution of Oxalic acid (using the mix ratio recommended for wood) which was used for this and during papering (see below), dipped a rag into the solution and, laying it down over the affected area, brought a hot iron to bear over the dent being careful to not singe the wood. The dents rose quickly to the level of the rest of the stock. (Don’t breathe the fumes of the evaporating vapors!)

Next came papering (sanding) the stock. In hindsight, I might have paid greater attention to how the head of the stock fitted the metalwork of the action. Beretta doesn’t do an aesthetically good job of this on their cheaper guns with the head largely over-sized for the action by several millimeters in places. It would have been a good opportunity to tidy this up. However, I didn’t notice beforehand and, since I had the metalwork off while sanding, I didn’t notice it until the metalwork was refitted prior to starting the finishing process.

Papering was the simple process starting at 180 grit and moving up through paper grades all the way to 2000 grit. (Actually, I did a light sand at 2500 grit, but I think this isn’t needed given all that follows.) All sanding was done dry even though wet ‘n dry paper was used. Between grades of paper, I ‘raised the grain’ by dampening the stock (excluding the checkering!) with the oxalic acid solution and then immediately drying it off with a heat gun. (See the Purdey video for a demonstration of this process.) The more we can lift the grain by doing this the smoother the wood will be once sanding is finished. The most tedious part of this entire process is filling in the remaining grain with finish and so the more we can do to make that easier the better. If you don’t want to use oxalic acid for this process (or raising dents) a solution of 75% ethanol alcohol/25% water will work.

Here’s a pic of what the wood looked like once papering was completed:

You must be absolutely meticulous throughout this preparation phase. Imperfections will come to haunt you later. Ask me how I know… Clean off the wood and give it a very close inspection. If there are spots or areas that you think can benefit from additional grain raising deal with them now. Here’s a couple of examples that should have been better dealt with early on. 40+ slacum applications later and they were still issues. I thought I had properly raised the dent at the top but a chip of damaged wood came out during sanding. The bit on the right looked deceptively innocent. Even more deceptive was the grain on the other side of the stock. Unfortunately I didn't photograph that.

The final part of this stage is to burnish the wood with a small amount of ‘red oil’ (more on this shortly) and a chamois.

Grain Filler

I don’t use a specific grain filler that would be sanded once dry. Instead, I use rottenstone combined with slacum to create a sort of dark cement in the grain. (See below.) This provides great local contrast. There exist, however, products that you can use at this stage – particularly if your wood has very open grain. I resisted the temptation to “cheat” but if you can’t fix difficult areas via raising and sanding then perhaps a grain filler has merit (particularly I troublesome areas). A grain filler will save a lot of work later but you may not get the ‘micro contrast’ of a grain that’s been filled with rottenstone and slacum.

Trade Secret (see below) make a grain filler intended for this process.

Last edited: