Unfortunately real and quite often, also all four flags going in different directions at the same time, the range is named old treacherous and it is. I have had times when the wind is coming towards me = POI going down and it has gone up. I think temperature change is also making things difficult. In Florida and start shooting at 8 am temp 41, 2 hours later it is at 62. Just a thought.

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

How much wind?

- Thread starter 86alaskan

- Start date

Bryan Litz has made a thorough treatment of the effects of wind variation along the direction of fire. Check out Chapter 5 in Applied Ballistics for Long Range Shooting, also Chapter 16 in Accuracy and Precision for Long Range Shooting. I believe there is a third chapter on the subject in his series Modern Advancements in Long Range shooting I (my copy is loaned out so I can't verify). He outlines several scenarios that he has tested - one in which the wind in the near field dominates the problem and another where the wind in the far field dominates the problem. His software allows you to input the wind profile along the course.

Shooter13

Gold $$ Contributor

I found it on Amazon for kindle for $14.99 and hardcover for $22.99 and paperback for $99.99!!!!!In their "The Wind Book for Rifle Shooters". Linda Miller and Keith Cunningham dedicate several pages to the discussion of how near and far winds affect the trajectory of the bullet. It is well explained, and there are many factors to consider. I bought this book for $18 from Amazon when I started in F-Class in September 2013 (*), and highly recommend it. However, it appears that it now is out-of-print, and the copies available are rather pricey. But if you can find one, it is an excellent book.

Alex

(*) PS. Thank you Immike (Mike J.) for recommending the book back then!

Longtrain

Gold $$ Contributor

I've been working on my winds skills lately...Thanks for any insight.

If we had no wind, we would all be High Masters.

Some shooters rely on mirage movement up to a certain wind velocity. I have found that range flags, properly deployed, have worked for me, along with mirage movement. At a recent 1K match, in which I did well, the flags told me to wait the condition out. I watched the flag twitch to the right a bit more then usual, didn’t feel it would matter to much, held left a bit, bang, just caught the 9 ring at 3 o’clock. From that point forward that flag told me to shoot or not.

BTW, the flags are even more fun when 3 or more point in different or opposite directions. Of course the flag closest to you has the most affect on your shot.

As you go to different ranges, wind, which is affected by topography of the range, your position on the line, mixed with all the environmental factors make each range a new PITA.

Ned Ludd

Silver $$ Contributor

I've been working on my winds skills lately. One thing has come up and I'm trying to get a handle on what to think about it. If I'm shooting LR, 500yds let's say, and there is wind, how much wind does it take to equate a full value correction at distance. If I have a full value 10mph 9 o"clock wind for the first 50yds from the firing line, but then absolutely no wind for the remaining 450yds, does that justify a full 10mph wind correction on the target? On the flip side, what if that 10mph is still 9 o'clock, but totally consistent for the entire 500yds? Will it push the bullet the calculated full value 10mph amount or more? Thanks for any insight.

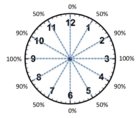

It sounds like you already are aware of this, but for a given wind angle relative to your line of sight, the effective wind value will be the absolute value of the sine of the angle multiplied by the wind speed. For example, the effective wind value of a 10 mph wind coming from 1:00 would be sin(30 degrees) x 10 mph = 5 mph. The easiest way to deal with the angles is to set up a chart that shows the effective values rounded to numbers easy to remember something like this:

With regard to how the wind varies over distance, that is much more subjective and often the best we can do is make an estimate of the wind over the length of the range that may or may not be correct. You can certainly use ballistic calculators such as JBM Ballistics (http://www.jbmballistics.com/cgi-bin/jbmtraj_simp-5.1.cgi) to estimate the effects of near wind versus far wind. Such programs will give you an actual number, but the real issue is not the math or accuracy of the prediction, it's the shooter's ability to correctly estimate the average wind speed across the entire trajectory of the bullet.

In general, wind close to the shooter will cause greater deflection than a comparable value wind speed close to the target. However, completely ignoring the wind near the target is a good way to shoot a poor score, because even though the effect of far wind may be a little less than near wind, it is not zero. This is where the subtleties of wind reading become important. You need to constantly evaluate all the information at your disposal. This might include obvious visual indicators such as wind flags, tree leaves, tall grass, etc., as well as the mirage visible in the spotting scope and/or rifle scope. The idea is to produce a mental estimate of the average wind over the length of the course and then make your shot adjustment accordingly. There is no substitute for doing this other than constant practice in varying wind conditions. One way to do this is to repeatedly make your best wind call, then send the shot. If your call was good, the impact will be close to where you wanted it to be. If not, your wind call likely needed improvement, and it is often possible upon closer inspection of the various indicators to figure out what was actually going on that you missed the first time. By repeatedly doing this in a variety of different wind conditions over time, your wind calls should improve. Unfortunately, this is not an exercise where you can expect to make quantum leaps in wind reading ability. It is much more realistic that you might notice a few months down the road that your wind calls in general have gotten better than they were before. It takes a lot of time and effort to improve these skills.

An additional layer of complexity in estimating wind effects is the terrain between the shooter and the target. For example, tall berms tend to increase elevation on the target in tailwind pickups as they cause the airstream to flow upwards as it goes over the berm. Likewise, tailwind let-offs will cause the impacts to drop. Having a good awareness of the terrain of the range and how different wind conditions may be affected by it is essential. Berms, valleys, breaks in a tree line, and other features of this sort need to be accounted for.

A final important aspect of wind reading that is worth mention is that sometimes, the best wind call you can make is simply to keep your finger off the trigger. If you see something happening with the condition you don't like, recognize, or understand, you're far better off waiting a bit to see if the previous condition returns, as it often will. Within reason, of course, you can only lose points when you pull the trigger, so deciding that a particular condition is not one in which you want to let a shot go is an important part of the learning process.

The good news is that you're asking the right questions. The more you get out and practice making wind calls, combined with critical evaluation and interpretation of why a particular wind call was not a good one, the better you will become at it.

JEFFPPC

Gold $$ Contributor

I would think the reason for that would be a large loss of velocity and large time of flight as you get closer to the 1000 yd line. I have found it a different challange from shooting short range 100,200.300 yd matches.The hardest part of reading the wind for long range competition is sifting through all the misinformation you receive on the internet.

I admit that I am no expert on the subject. But I can promise you when you are competing at 1000 yards if you are paying more attention to what's happening 30 yards out than you are to what's going on about 800 yards out you most likely will get beat.

I know that goes against most the math and the experts, but it is true.

Use this windchart as a template for other bullets and muzzle velocities by using JBM http://www.jbmballistics.com/cgi-bin/jbmtraj_drift-5.1.cgi to replace the values in column I for wind drift at 10mph.

Attachments

Similar threads

- Replies

- 6

- Views

- 1,019

Upgrades & Donations

This Forum's expenses are primarily paid by member contributions. You can upgrade your Forum membership in seconds. Gold and Silver members get unlimited FREE classifieds for one year. Gold members can upload custom avatars.

Click Upgrade Membership Button ABOVE to get Gold or Silver Status.

You can also donate any amount, large or small, with the button below. Include your Forum Name in the PayPal Notes field.

To DONATE by CHECK, or make a recurring donation, CLICK HERE to learn how.

Click Upgrade Membership Button ABOVE to get Gold or Silver Status.

You can also donate any amount, large or small, with the button below. Include your Forum Name in the PayPal Notes field.

To DONATE by CHECK, or make a recurring donation, CLICK HERE to learn how.