We don’t need a chart in seconds . Why do you suggest that ? We need to know what the mass the material in the chart above is based on , not what happens to that brass in seconds.

Hang on a second. Let's take a step back.

The majority of charts you see in metallurgical books on brass alloys are for a puck. It literally looks like a little 1/4" thick disc, like a little hockey puck. It needs to be easy to prepare for microscopy to study the grain size, and to be ready for hardness tests.

Many types of handy samples have to do with other common tests that have nothing to do with making cartridge cases, but are used for proving the quality controls of the alloy are met. Those samples are not useful for proving what happens to a cartridge case during manufacture or to reloading.

Not to start an argument or debate, but yes we do actually care about seconds, not hours or even minutes.

We don't want to soak a cartridge case and ruin the case head or body, but we do need do three things to keep this under control. 1) Heat Flux Rate, 2) Peak Temperature, 3) Time.

First, we have to do this at the neck and it can go down past the shoulder, but should not affect the body. That means we don't have a lot of time to get the neck into annealing temps before the heat would go down the body. So, the heat flux rate has to meet some minimums and also meet some temperatures that can work fast.

Yes, than means we are in that 750 neighborhood or higher if we want to get the annealing done within seconds. If we go very much higher, we start to oxidize the alloys, and you will see the zinc oxides start to surface. If we take too long, the shoulders and body get softer than we want.

We don't have many great options for measuring transient temperatures. The human eye can begin to see the infrared heat when the brass jut happens to get to near 750, which is a useful temperature cause it only takes a heartbeat at or above that temp to get to our goals. All of the time above about 400 counts, but the higher temps count for much more as the temp gets closer to or above 750. If you happened to hit 1000 it isn't the end of the world as long as you didn't stay there for more than a blink. Any higher or longer and you will over anneal, which again isn't instant death but would be a reject on a production line.

To anneal at home, you need to be able to find that initial glow point. It helps to avoid heating so fast that you go right past it. With a flame, I would rather call it to within 0.1 seconds on a 7 second rate, than call it to 0.1 seconds on a 3 second rate and have it climb so fast it overshoots. You will get much tighter results with the 7 second heat flux rate since you can be off just a little without over or undershooting. You also don't want to go so slow that the case body starts to soften.

For most metals with a typical emissivity, these are rough values in degrees F, but as you can surmise they are as good as Tempilaq.

750 -- Red heat, dull glow just visible in the dark

885 -- Red heat, visible in the low light (gas flame is dimmer that this, but brighter than dark)

975 -- Red heat, visible in room light

1100 - Red heat, visible in direct sunlight

1300 - Dark red

1500 - Dull cherry-red

1650 - Cherry-red

1800 - Bright cherry-red

2000 - Orange-red

We have used all sorts of methods to anneal in production, and at home. You can hit the numbers with a flame, or using induction. Spotting a dull glow in a darkened room with the torch should put you between 750 and 885 F.

Depending on the thickness of the brass and case size, it just takes a moment at those temps to get the hardness value down below 120. It takes actual HV testing to know the exact amount of time at, above, or below that glow point to hit the perfect value. Good annealing doesn't have to be an exact value but a consistent one below 120 will meet the goals.

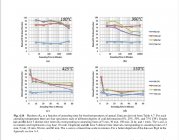

The goals of cartridge brass annealing look something like this. We try to stay in between the lines. Cases don't explode if we are off a little, but the whole idea here in this context is to try and get it right.

Keeping the HV inside those lines just means you will look more like the virgin brass. A little higher or lower is okay, but the idea is to make it consistent for seating and tension. It will typically fall inside those lines when the heat flux rate, max temp, and time to temp, are good.

If you are not disciplined about the heat flux rate, the peak temp, or the time, you are better off not doing this at all. You can send your samples to a lab for testing, or you can compare your annealing to virgin brass in rough terms by seating force.

Slide prep and hardness surveys are not cheap, so if you can't handle the discipline of annealing, you can live without it. As is often the case with reloading.... YMMV