Jager

Gold $$ Contributor

The shot breaks clean, an echo from across the years. As the rifle comes out of recoil the first thing my eyes see is the magnified image of the target. Good. The 90gr Scenar-L POI is not far from the POI of the 100gr Winchester factory rounds I have dialed the scope in with.

The scope zero will be fine for this ladder.

But then my eye shifts to the screen of the LabRadar. In large numerals, ‘2675’ stares back at me.

Huh?

My hand reaches across and extracts the card from the lid of the box. No, I’m not dreaming. The load should be making 2950 fps, and just over 50K psi.

One more glance at the LabRadar. Four bars of signal. That was a good read.

Mentally shrugging, I send the next two rounds. They’re low too.

Working slowly up the ladder, the progression of velocity and pressure continues in lockstep. Everything is orderly. There are no surprises. Other than that everything is between 200 and 250 fps slower than it should be.

Forty years ago when we wanted to develop a load, we’d spread out an assortment of loading manuals, pore over data for the exact bullet if we were lucky, or a close analog if we weren’t, and begin to narrow in on what might work. Extrapolating all that data to our own rifle, we’d guestimate velocity and pressure. Chronographs were around, but very few shooters had access to one. The numbers written in the load manuals were our proxy. The old three-ring binder that served as my handload log for so many years had countless “EV” – estimated velocity – references.

Then we’d head to the bench and put together what John Wooters called a pressure series. What we today call a ladder.

A lot of really good ammo got made that way. And a fair bit of not-so-good, as well.

Most of us never really knew what we had. We could see groups, of course. How accurate a load was. And how it performed on game. But when the book said the max load was x grains of y powder, and that load would give you this velocity at that pressure… you pretty much had to take it at its word.

The problem I’m having here, today, now – a series of loads, each performing a couple hundred feet per second slower than it should – would probably have gone undetected. Shot at distance, the verticals would tell the tale. But most of us would have just shrugged and concluded it was one more marketing-department-inspired ballistic coefficient writing a check that the real world could never cash. We’d assume that our muzzle velocity was pretty close to that ‘EV’ we had happily written down.

Two things changed all that for me: Affordable, accurate chronographs. And QuickLoad.

Used together, they give shooters a glimpse into what historically has been a black box. They give us insight into the actual pressures we are running.

In this case I was using an old rifle – the oldest centerfire rifle I own, a Model 70 in .243 Win, purchased new when I was a very young man – but not fired in 37 years. But I would be using a new bullet – a Lapua 90gr Scenar-L. And a new powder – Accurate 4350. The dozens of loads I conocted for the rifle back in the day didn’t matter. This was new in every way that mattered.

I model the loads I intend to build in QuickLoad, before I ever weigh the first charge. If it’s a powder I’ve already calibrated, and the cartridge context is similar, I am entirely comfortable going straight to near-maximum load. Or even a slightly over-maximum load. Ladders are for finding accuracy nodes, not for discovering where the pressure limit is.

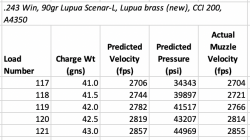

If it’s an uncalibrated powder/cartridge context, then you’re left with running QuickLoad defaults. You do that knowing that what it tells you is going to be off, but will probably be in the ballpark. My current Handload Log – now electronic – includes columns not just for “Predicted Velocity” and “Predicted Pressure,” but also for “Adjusted Prediction – Velocity” and “Adjusted Prediction – Pressure.” Real world chrono data lets you tweak QuickLoad so that its predictions are reflective of what, in fact, you are going to get.

None of which is to suggest that load manuals no longer have a place. To the contrary, they are gold mines of information. The thousands of hours of ballistics lab hours that went into their making are simply priceless.

Lapua does not provide load data on their bullets. The Berger 90gr Match BT Target bullet is very similar to the Scenar-L, though, and Berger’s max load for their bullet, using IMR-4350 (similar to A4350), is 42.6, producing 3033 fps.

Another analog is the Sierra 90gr TGK. Sierra lists max for that bullet, using the exact same A4350 powder as I intend, at 43.7, producing 3140 fps.

So with those two book loads in hand as supporting evidence, I was entirely comfortable with QuickLoad’s (default) prediction that 43.0/A4350 would produce something in the neighborhood of 3100 fps at around 59,000 psi. That was my max.

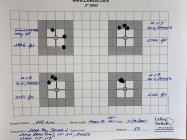

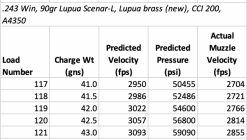

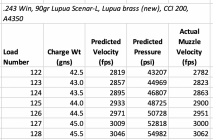

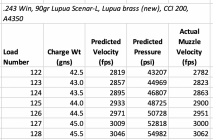

The whole ladder:

My dilemma here, then, the thing that gave me pause… was that adjusting QuickLoad so that it would match real world velocities involved much more than a “tweak.”

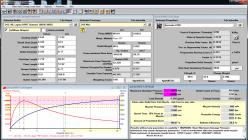

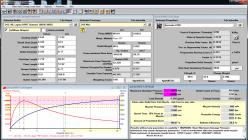

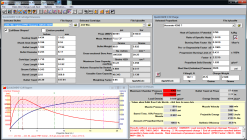

The primary mechanism QuickLoad uses for adjusting its results, for calibrating it, is an editable element called Burning Rate Factor. Each powder is different. When you select A4350, the program default is 0.3810. Adjusting it until the program predictions closely mirror actual chrono data requires bringing it down to the neighborhood of 0.3365. That is a staggering amount of change.

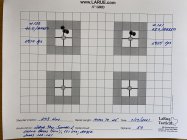

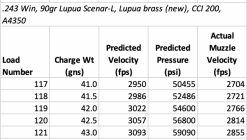

But putting aside my squinty eyed look for a moment, and dutifully following my process, making that Burning Rate Factor change, makes that same ladder look like this:

The obvious inference from this view is that the reason my actual velocities were down is because I was actually running quite mild pressures. And that there’s still plenty of room before approaching SAAMI max.

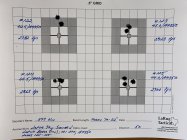

And, yet, Berger and Sierra would seemingly beg to differ. Their 42.6 and 43.7 max, respectively, is difficult to dismiss. Get it wrong and an extended-ladder max charge could look like this:

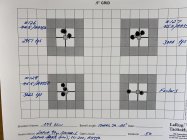

Sleeping on it, I wake knowing what I’m going to do. Firing up the AutoTrickler, I quickly put together 21 fresh rounds:

New School.

The scope zero will be fine for this ladder.

But then my eye shifts to the screen of the LabRadar. In large numerals, ‘2675’ stares back at me.

Huh?

My hand reaches across and extracts the card from the lid of the box. No, I’m not dreaming. The load should be making 2950 fps, and just over 50K psi.

One more glance at the LabRadar. Four bars of signal. That was a good read.

Mentally shrugging, I send the next two rounds. They’re low too.

Working slowly up the ladder, the progression of velocity and pressure continues in lockstep. Everything is orderly. There are no surprises. Other than that everything is between 200 and 250 fps slower than it should be.

Forty years ago when we wanted to develop a load, we’d spread out an assortment of loading manuals, pore over data for the exact bullet if we were lucky, or a close analog if we weren’t, and begin to narrow in on what might work. Extrapolating all that data to our own rifle, we’d guestimate velocity and pressure. Chronographs were around, but very few shooters had access to one. The numbers written in the load manuals were our proxy. The old three-ring binder that served as my handload log for so many years had countless “EV” – estimated velocity – references.

Then we’d head to the bench and put together what John Wooters called a pressure series. What we today call a ladder.

A lot of really good ammo got made that way. And a fair bit of not-so-good, as well.

Most of us never really knew what we had. We could see groups, of course. How accurate a load was. And how it performed on game. But when the book said the max load was x grains of y powder, and that load would give you this velocity at that pressure… you pretty much had to take it at its word.

The problem I’m having here, today, now – a series of loads, each performing a couple hundred feet per second slower than it should – would probably have gone undetected. Shot at distance, the verticals would tell the tale. But most of us would have just shrugged and concluded it was one more marketing-department-inspired ballistic coefficient writing a check that the real world could never cash. We’d assume that our muzzle velocity was pretty close to that ‘EV’ we had happily written down.

Two things changed all that for me: Affordable, accurate chronographs. And QuickLoad.

Used together, they give shooters a glimpse into what historically has been a black box. They give us insight into the actual pressures we are running.

In this case I was using an old rifle – the oldest centerfire rifle I own, a Model 70 in .243 Win, purchased new when I was a very young man – but not fired in 37 years. But I would be using a new bullet – a Lapua 90gr Scenar-L. And a new powder – Accurate 4350. The dozens of loads I conocted for the rifle back in the day didn’t matter. This was new in every way that mattered.

I model the loads I intend to build in QuickLoad, before I ever weigh the first charge. If it’s a powder I’ve already calibrated, and the cartridge context is similar, I am entirely comfortable going straight to near-maximum load. Or even a slightly over-maximum load. Ladders are for finding accuracy nodes, not for discovering where the pressure limit is.

If it’s an uncalibrated powder/cartridge context, then you’re left with running QuickLoad defaults. You do that knowing that what it tells you is going to be off, but will probably be in the ballpark. My current Handload Log – now electronic – includes columns not just for “Predicted Velocity” and “Predicted Pressure,” but also for “Adjusted Prediction – Velocity” and “Adjusted Prediction – Pressure.” Real world chrono data lets you tweak QuickLoad so that its predictions are reflective of what, in fact, you are going to get.

None of which is to suggest that load manuals no longer have a place. To the contrary, they are gold mines of information. The thousands of hours of ballistics lab hours that went into their making are simply priceless.

Lapua does not provide load data on their bullets. The Berger 90gr Match BT Target bullet is very similar to the Scenar-L, though, and Berger’s max load for their bullet, using IMR-4350 (similar to A4350), is 42.6, producing 3033 fps.

Another analog is the Sierra 90gr TGK. Sierra lists max for that bullet, using the exact same A4350 powder as I intend, at 43.7, producing 3140 fps.

So with those two book loads in hand as supporting evidence, I was entirely comfortable with QuickLoad’s (default) prediction that 43.0/A4350 would produce something in the neighborhood of 3100 fps at around 59,000 psi. That was my max.

The whole ladder:

My dilemma here, then, the thing that gave me pause… was that adjusting QuickLoad so that it would match real world velocities involved much more than a “tweak.”

The primary mechanism QuickLoad uses for adjusting its results, for calibrating it, is an editable element called Burning Rate Factor. Each powder is different. When you select A4350, the program default is 0.3810. Adjusting it until the program predictions closely mirror actual chrono data requires bringing it down to the neighborhood of 0.3365. That is a staggering amount of change.

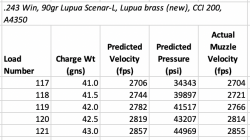

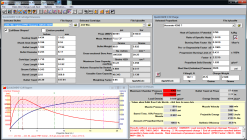

But putting aside my squinty eyed look for a moment, and dutifully following my process, making that Burning Rate Factor change, makes that same ladder look like this:

The obvious inference from this view is that the reason my actual velocities were down is because I was actually running quite mild pressures. And that there’s still plenty of room before approaching SAAMI max.

And, yet, Berger and Sierra would seemingly beg to differ. Their 42.6 and 43.7 max, respectively, is difficult to dismiss. Get it wrong and an extended-ladder max charge could look like this:

Sleeping on it, I wake knowing what I’m going to do. Firing up the AutoTrickler, I quickly put together 21 fresh rounds:

New School.

Last edited: