Jager

Gold $$ Contributor

The short answer, for those in a hurry, is an unequivocal ‘yes.’

But the whole story is a little more nuanced than that. The new Garmin is not perfect. And it’s important to remember that the LabRadar, the AndiScan, the MagnetoSpeed, and all the other chronographs out there continue to perform every bit as well today as they did ten days ago when the Garmin made its appearance. If those are meeting your need, there’s absolutely no need to part with another $600.

But for those of us who use a chronograph all the time, the Garmin Xero brings an awful lot to the table.

I wrote a few lines comparing the LabRadar with the AndiScan a few months ago (https://forum.accurateshooter.com/t...ograph-labradar-killer.4100134/#post-38707020). I won’t repeat all that, other than to reiterate that I was, and remain, an ardent fan of the LabRadar. My experience with that unit has been overwhelmingly positive, across many years and many tens of thousands of rounds.

What the doppler technology in LabRadar gave us, compared to the mostly optical chronos that preceded it, was a huge leap in convenience. Suddenly, using a chronograph was quick and easy, with all setup happening behind the line of fire.

When the AndiScan came along a year ago, its tiny form factor promised to extend that convenience even further, even if its breathtaking $1,000 price tag meant that it would always remain a niche product. Alas, the AndiScan was handicapped by what may be the most hideous user interface I’ve ever seen.

It’s only with the Garmin Xero that we finally see the realization of a reliable, easy to use, tiny-form-factor doppler chronograph. Garmin still has some work to do – more on that shortly – but this first effort has absolutely moved the goal posts.

First thing, the Garmin is ready to use, right out of the box. The tiny, little tabletop tripod it ships with is cheap plastic, but entirely serviceable. Both the LabRadar and the AndiScan require you to first bring some sort of mounting solution to bear. In the early years with the LabRadar I used their expensive tabletop mounting plate, later moving to a photography tripod placed in front of my shooting bench. With the AndiScan I ordered a cheap $20 tabletop tripod from Amazon. Neither was difficult to do, but it’s a nice touch that the Garmin is ready to go when you receive it.

The Garmin is rated IPX7 for water resistance. That’s one meter of immersion, for 30 minutes. That’s an important consideration for those of us who occasionally end up shooting in wet weather… and is the only one among this trio that has that quality.

The Garmin also includes a decent internal Li-ion battery. Among this trio of doppler chronos, it’s the first one that doesn’t suck, reputedly offering up to six hours of charge. If that’s not enough, you can plug an external battery pack into the unit’s USB-C port. The only downside I see with the Garmin’s battery is that it’s not user replaceable (not that it can’t be replaced by a user… like replacing the battery in your laptop or smartphone, it can be done by a knowledgeable and intrepid user… but it’s not designed for that and most owners will probably end up shipping their unit back to Garmin).

Similar to the LabRadar, the Garmin comes with a free smartphone/tablet app called ShotView. Pairing the Xero is dead simple. And performing firmware updates via that ShotView app couldn’t be easier. The Bluetooth connection between ShotView and the Xero also seems far more reliable than the all-too-flakey Bluetooth connection implemented by LabRadar. But, in its first disappointment, that ShotView app is required to offload data from the Garmin. The Xero can be used as a standalone unit for capturing data. But to later get that data into a computer requires a smartphone. Like the AndiScan, the Xero fails to make use of its USB-C port for data transfer.

All three doppler chronographs operate in the 24 GHz band. Think K-band police radar, along with consumer-grade things like automatic door openers, vehicle blind spot monitoring systems, and the like.

Compared to the LabRadar’s transmit output power of 4.84 dBm (U.S. version), and the AndiScan’s 11 dBm, the Xero bumps that transmit power level considerably, to 18.68 dBm.

For context, 0 dBm is 1 milliwatt. The typical cell phone transmits at around 23 dBm. And a portable 5-watt ham radio transceiver is putting out 37 dBm.

One benefit of the Garmin’s extra output power (in addition, no doubt, to improved digital signal processing) is its 5,000 fps velocity ceiling. That’s well above the AndiScan’s 4295 fps limit, and the LabRadar’s 3900 fps limit. Whatever rifle you want to measure, the Garmin’s ceiling is never going to be the limiting factor.

All three chronos consistently track each other. A rise of a few fps in velocity, or a dip, is appropriately and proportionally reflected on each. I would call them dead equal in accuracy.

Positioning is another matter.

The Garmin specs a very simple 5-15” distance from the muzzle (towards the shooter); and a 5-15” offset from the barrel. Given its single spec, the Garmin does not offer any kind of internal configuration setting for a different positioning. That very simple, easy-to-understand 5-15” positioning spec might sound way cool. But hold that thought…

The LabRadar provides three “projectile offset” options: 6” if the muzzle is 1-6” from the side of the LabRadar; 12” if the muzzle is 7-12”; and 18” if the muzzle is 13-18”. All three of these are essentially barrel offsets. And those three offset specs are all pretty sloppy, given the 6” range they each encompass. The LabRadar does not provide any configurable option for distance-from-muzzle, either forward towards the target, or backwards towards the shooter.

The AndiScan is the only one that truly gets it right with respect to chrono positioning, offering highly configurable menu settings for both barrel offset and distance-from-muzzle. And a section in their user manual that describes in some depth why that matters.

There’s no magic to this. A doppler chronograph is always going to be offset from the bore. And because of that, the bullet will not enter the chrono’s radar signal path until some distance downrange – typically a few feet. The chrono then has to have an algorithm to back-calculate the speed back at the muzzle. That calculation is very straightforward – and very precise – if the exact position of the chronograph is known. In the case of the LabRadar, their positioning spec (with their three pretty sloppy barrel offset settings; and a single setting – even with the muzzle – for distance-from-muzzle) injects a modest degree of variance. The Garmin (with its single 5-15” spec for both barrel offset and distance-from-muzzle) injects even more.

Does any of this even matter? Probably not. The degree of potential error we’re talking about is not large. Probably not more than 10 fps in most cases. And if a shooter is always careful to position his doppler chrono in the same relative position on his bench every time, his relative results will be perfectly fine.

I mention all this not to be overly anal (although perhaps I am!), but because it’s obvious that in their design brief Garmin prioritized ease-of-use over ultimate accuracy. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. But in our collective (and warranted!) enthusiasm over the new Xero, I think it’s helpful to try and remain objective. Garmin did not invent a math-and-physics Unicorn.

Without any configurable way of adjusting their position algorithm, the only way a Xero owner has to true up to another device, like, say, a long-used LabRadar, is to experiment with placement. Moving the Xero fore and aft, from up near the muzzle to back near the shooter; and further or closer from the barrel, will tweak how close the numbers from the Garmin are to those from the other chronograph.

What I can say is that my initial position – up near the muzzle, just in front of my front rest – gave me a consistent ~4 fps delta between the Xero and my LabRadar. I’m happy enough with that to call it good.

Related to positioning, Garmin also dispensed with any sort of signal response indication. Both the LabRadar and the AndiScan have this feature – letting you know how well, or not, the bullet you just sent downrange was picked up and received by the chronograph. Over the years, I found that feature indispensable with my LabRadar, letting me know when/if my positioning might have gone a little bit sideways before I actually began to lose shots. I wish the Garmin had some sort of similar indicator, but honestly it might simply be unnecessary. The Xero appears to be far more robust at picking up shots and it might simply not need the kind of very precise pointing-at-the-target positioning that the LabRadar demands. That’s probably down to the much higher transmit signal strength of the Garmin.

The Garmin also does not give the option of selecting multiple frequency channels, as both the LabRadar and AndiScan do. Nor does it provide configurable receiver detection sensitivity settings, where the LabRadar lets you choose between eight values and the AndiScan lets you choose between four. The reason these two options might be important is to prevent collisions with other doppler radar units in close proximity. Whether that might ever be a problem is an open question. There are other design approaches one could implement to partially mitigate that problem. Garmin’s Owner’s Manual and marketing materials are silent on that matter, so we’ll just have to wait and see once more units are in the field.

In what may be the most interesting technical innovation in the Xero, Garmin dispensed with the acoustic trigger found in both the LabRadar and the AndiScan. It appears the Garmin simply waits for a projectile to enter its signal path, rejecting objects that are outside its minimum and maximum velocity range (such as people walking in front of it, blowing leaves, etc.). The benefit here is the ability to capture projectiles from relatively quiet sources such as suppressed rifles and air guns. That likely also enhances the unit’s shot-to-shot reliability, since it’s not depending upon an acoustic triggering event upstream of the signal path processing – and the critical timing between those two elements.

The Garmin Xero is an utter joy to use. It sets up in about as much time as it takes you to say it. And then it just sits there quietly reporting every shot you take. Without hiccup. Without drama.

Its ergonomics and its user interface are everything the LabRadar and the AndiScan could have been, but never were. You can (and should) read the Xero’s fairly short Owner’s Manual. But you don’t have to. Its interface is simple enough and intuitive enough that it’s super easy to figure out. As Apple used to say… it just works.

When you’re done shooting… well, here we get to my biggest disappointment.

The LabRadar writes its CSV files to an SD card. Pop that card out, plug it into your computer, offload the files, delete the files from the card, and plug it back into the LabRadar. Easy peasy.

The AndiScan, with its inscrutable WiFi interface, is the complete opposite. I described that interface as an abortion in my earlier missive, and I stand by that.

The Garmin is somewhere between the two. First, although you can directly plug the Garmin into your computer via its USB-C port, and the Garmin will then dutifully appear on your machine as a removable drive which you can navigate… you’ll quickly discover that the folder containing your shot data is written not to CSV files… but to FIT files. FIT stands for Flexible and Interoperable Data Transfer and is a proprietary Garmin protocol. The files are binary. They have been used for years in Garmin’s health-related products like their smart watches. So it’s not surprising – disappointing, but not surprising – that they would use that same format in this new chronograph. Garmin’s developers were already familiar with FIT, after all.

The challenge is that although it’s very simple to copy and paste those FIT files off your Xero and into your computer, in order to actually use those files requires first translating them to CSV or some other file format accessible to Excel or the like.

I’m not going to belabor this… suffice it to say that although Garmin provides both a software developers kit (SDK) as well as a command line Java utility called FitCSVTool which purports to do that kind of binary-to-text conversion, my initial evaluation of that tool appears to show that the FIT files created by the Xero are not exactly the same as those created by Garmin’s health-related products.

The bottom line for me, and I suspect for most of us, is that FIT files are pretty useless. And so getting them onto our computer via the Xero’s USB-C port is a wasted effort.

The good news is that Garmin’s ShotView app is as simple to use, is as intuitive, as is the Xero unit itself. And ShotView has a feature for exporting a shot series to CSV, and thence out to your computer, via text, email, or AirDrop.

It’s quick and easy. And especially if you’re a shooter who habitually shoots only one or a couple of long sessions – all or most shots in one series, in other words – it’s almost a non-issue.

For those of us who do a lot of load development, though, who almost always come back with a fair number of different shot series, you’ll have to click through each series in turn, exporting them one at a time.

It’s not a big deal. But it shouldn’t be necessary.

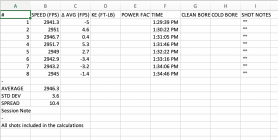

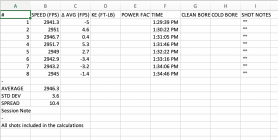

Once you get the files exported and onto your computer, they’re fine. Here’s what the the Garmin file looks like, followed by the exact same shot series collected by the LabRadar.

And, finally, here is a size comparison. From left-to-right, the LabRadar, the Garmin Xero, the AndiScan (with its supplied case in front of it), and the FXAir (airguns only).

In sum, the new Garmin Xero Pro C1 is not perfect. But it’s close. What faults it has are really quite minor, niggles on an otherwise exemplary product. It’s what the LabRadar might have ended up looking like had Infinition continued to develop their product.

The AndiScan had the form factor, but failed on the rest of it.

I speak of both those chronographs in the past tense, because there’s no doubt in my mind that they are both done. I love them both. The LabRadar, in particular, has been my steadfast companion for what seems like an eon. But they are both done.

Now, like there once was, there is only one.

But the whole story is a little more nuanced than that. The new Garmin is not perfect. And it’s important to remember that the LabRadar, the AndiScan, the MagnetoSpeed, and all the other chronographs out there continue to perform every bit as well today as they did ten days ago when the Garmin made its appearance. If those are meeting your need, there’s absolutely no need to part with another $600.

But for those of us who use a chronograph all the time, the Garmin Xero brings an awful lot to the table.

I wrote a few lines comparing the LabRadar with the AndiScan a few months ago (https://forum.accurateshooter.com/t...ograph-labradar-killer.4100134/#post-38707020). I won’t repeat all that, other than to reiterate that I was, and remain, an ardent fan of the LabRadar. My experience with that unit has been overwhelmingly positive, across many years and many tens of thousands of rounds.

What the doppler technology in LabRadar gave us, compared to the mostly optical chronos that preceded it, was a huge leap in convenience. Suddenly, using a chronograph was quick and easy, with all setup happening behind the line of fire.

When the AndiScan came along a year ago, its tiny form factor promised to extend that convenience even further, even if its breathtaking $1,000 price tag meant that it would always remain a niche product. Alas, the AndiScan was handicapped by what may be the most hideous user interface I’ve ever seen.

It’s only with the Garmin Xero that we finally see the realization of a reliable, easy to use, tiny-form-factor doppler chronograph. Garmin still has some work to do – more on that shortly – but this first effort has absolutely moved the goal posts.

First thing, the Garmin is ready to use, right out of the box. The tiny, little tabletop tripod it ships with is cheap plastic, but entirely serviceable. Both the LabRadar and the AndiScan require you to first bring some sort of mounting solution to bear. In the early years with the LabRadar I used their expensive tabletop mounting plate, later moving to a photography tripod placed in front of my shooting bench. With the AndiScan I ordered a cheap $20 tabletop tripod from Amazon. Neither was difficult to do, but it’s a nice touch that the Garmin is ready to go when you receive it.

The Garmin is rated IPX7 for water resistance. That’s one meter of immersion, for 30 minutes. That’s an important consideration for those of us who occasionally end up shooting in wet weather… and is the only one among this trio that has that quality.

The Garmin also includes a decent internal Li-ion battery. Among this trio of doppler chronos, it’s the first one that doesn’t suck, reputedly offering up to six hours of charge. If that’s not enough, you can plug an external battery pack into the unit’s USB-C port. The only downside I see with the Garmin’s battery is that it’s not user replaceable (not that it can’t be replaced by a user… like replacing the battery in your laptop or smartphone, it can be done by a knowledgeable and intrepid user… but it’s not designed for that and most owners will probably end up shipping their unit back to Garmin).

Similar to the LabRadar, the Garmin comes with a free smartphone/tablet app called ShotView. Pairing the Xero is dead simple. And performing firmware updates via that ShotView app couldn’t be easier. The Bluetooth connection between ShotView and the Xero also seems far more reliable than the all-too-flakey Bluetooth connection implemented by LabRadar. But, in its first disappointment, that ShotView app is required to offload data from the Garmin. The Xero can be used as a standalone unit for capturing data. But to later get that data into a computer requires a smartphone. Like the AndiScan, the Xero fails to make use of its USB-C port for data transfer.

All three doppler chronographs operate in the 24 GHz band. Think K-band police radar, along with consumer-grade things like automatic door openers, vehicle blind spot monitoring systems, and the like.

Compared to the LabRadar’s transmit output power of 4.84 dBm (U.S. version), and the AndiScan’s 11 dBm, the Xero bumps that transmit power level considerably, to 18.68 dBm.

For context, 0 dBm is 1 milliwatt. The typical cell phone transmits at around 23 dBm. And a portable 5-watt ham radio transceiver is putting out 37 dBm.

One benefit of the Garmin’s extra output power (in addition, no doubt, to improved digital signal processing) is its 5,000 fps velocity ceiling. That’s well above the AndiScan’s 4295 fps limit, and the LabRadar’s 3900 fps limit. Whatever rifle you want to measure, the Garmin’s ceiling is never going to be the limiting factor.

All three chronos consistently track each other. A rise of a few fps in velocity, or a dip, is appropriately and proportionally reflected on each. I would call them dead equal in accuracy.

Positioning is another matter.

The Garmin specs a very simple 5-15” distance from the muzzle (towards the shooter); and a 5-15” offset from the barrel. Given its single spec, the Garmin does not offer any kind of internal configuration setting for a different positioning. That very simple, easy-to-understand 5-15” positioning spec might sound way cool. But hold that thought…

The LabRadar provides three “projectile offset” options: 6” if the muzzle is 1-6” from the side of the LabRadar; 12” if the muzzle is 7-12”; and 18” if the muzzle is 13-18”. All three of these are essentially barrel offsets. And those three offset specs are all pretty sloppy, given the 6” range they each encompass. The LabRadar does not provide any configurable option for distance-from-muzzle, either forward towards the target, or backwards towards the shooter.

The AndiScan is the only one that truly gets it right with respect to chrono positioning, offering highly configurable menu settings for both barrel offset and distance-from-muzzle. And a section in their user manual that describes in some depth why that matters.

There’s no magic to this. A doppler chronograph is always going to be offset from the bore. And because of that, the bullet will not enter the chrono’s radar signal path until some distance downrange – typically a few feet. The chrono then has to have an algorithm to back-calculate the speed back at the muzzle. That calculation is very straightforward – and very precise – if the exact position of the chronograph is known. In the case of the LabRadar, their positioning spec (with their three pretty sloppy barrel offset settings; and a single setting – even with the muzzle – for distance-from-muzzle) injects a modest degree of variance. The Garmin (with its single 5-15” spec for both barrel offset and distance-from-muzzle) injects even more.

Does any of this even matter? Probably not. The degree of potential error we’re talking about is not large. Probably not more than 10 fps in most cases. And if a shooter is always careful to position his doppler chrono in the same relative position on his bench every time, his relative results will be perfectly fine.

I mention all this not to be overly anal (although perhaps I am!), but because it’s obvious that in their design brief Garmin prioritized ease-of-use over ultimate accuracy. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. But in our collective (and warranted!) enthusiasm over the new Xero, I think it’s helpful to try and remain objective. Garmin did not invent a math-and-physics Unicorn.

Without any configurable way of adjusting their position algorithm, the only way a Xero owner has to true up to another device, like, say, a long-used LabRadar, is to experiment with placement. Moving the Xero fore and aft, from up near the muzzle to back near the shooter; and further or closer from the barrel, will tweak how close the numbers from the Garmin are to those from the other chronograph.

What I can say is that my initial position – up near the muzzle, just in front of my front rest – gave me a consistent ~4 fps delta between the Xero and my LabRadar. I’m happy enough with that to call it good.

Related to positioning, Garmin also dispensed with any sort of signal response indication. Both the LabRadar and the AndiScan have this feature – letting you know how well, or not, the bullet you just sent downrange was picked up and received by the chronograph. Over the years, I found that feature indispensable with my LabRadar, letting me know when/if my positioning might have gone a little bit sideways before I actually began to lose shots. I wish the Garmin had some sort of similar indicator, but honestly it might simply be unnecessary. The Xero appears to be far more robust at picking up shots and it might simply not need the kind of very precise pointing-at-the-target positioning that the LabRadar demands. That’s probably down to the much higher transmit signal strength of the Garmin.

The Garmin also does not give the option of selecting multiple frequency channels, as both the LabRadar and AndiScan do. Nor does it provide configurable receiver detection sensitivity settings, where the LabRadar lets you choose between eight values and the AndiScan lets you choose between four. The reason these two options might be important is to prevent collisions with other doppler radar units in close proximity. Whether that might ever be a problem is an open question. There are other design approaches one could implement to partially mitigate that problem. Garmin’s Owner’s Manual and marketing materials are silent on that matter, so we’ll just have to wait and see once more units are in the field.

In what may be the most interesting technical innovation in the Xero, Garmin dispensed with the acoustic trigger found in both the LabRadar and the AndiScan. It appears the Garmin simply waits for a projectile to enter its signal path, rejecting objects that are outside its minimum and maximum velocity range (such as people walking in front of it, blowing leaves, etc.). The benefit here is the ability to capture projectiles from relatively quiet sources such as suppressed rifles and air guns. That likely also enhances the unit’s shot-to-shot reliability, since it’s not depending upon an acoustic triggering event upstream of the signal path processing – and the critical timing between those two elements.

The Garmin Xero is an utter joy to use. It sets up in about as much time as it takes you to say it. And then it just sits there quietly reporting every shot you take. Without hiccup. Without drama.

Its ergonomics and its user interface are everything the LabRadar and the AndiScan could have been, but never were. You can (and should) read the Xero’s fairly short Owner’s Manual. But you don’t have to. Its interface is simple enough and intuitive enough that it’s super easy to figure out. As Apple used to say… it just works.

When you’re done shooting… well, here we get to my biggest disappointment.

The LabRadar writes its CSV files to an SD card. Pop that card out, plug it into your computer, offload the files, delete the files from the card, and plug it back into the LabRadar. Easy peasy.

The AndiScan, with its inscrutable WiFi interface, is the complete opposite. I described that interface as an abortion in my earlier missive, and I stand by that.

The Garmin is somewhere between the two. First, although you can directly plug the Garmin into your computer via its USB-C port, and the Garmin will then dutifully appear on your machine as a removable drive which you can navigate… you’ll quickly discover that the folder containing your shot data is written not to CSV files… but to FIT files. FIT stands for Flexible and Interoperable Data Transfer and is a proprietary Garmin protocol. The files are binary. They have been used for years in Garmin’s health-related products like their smart watches. So it’s not surprising – disappointing, but not surprising – that they would use that same format in this new chronograph. Garmin’s developers were already familiar with FIT, after all.

The challenge is that although it’s very simple to copy and paste those FIT files off your Xero and into your computer, in order to actually use those files requires first translating them to CSV or some other file format accessible to Excel or the like.

I’m not going to belabor this… suffice it to say that although Garmin provides both a software developers kit (SDK) as well as a command line Java utility called FitCSVTool which purports to do that kind of binary-to-text conversion, my initial evaluation of that tool appears to show that the FIT files created by the Xero are not exactly the same as those created by Garmin’s health-related products.

The bottom line for me, and I suspect for most of us, is that FIT files are pretty useless. And so getting them onto our computer via the Xero’s USB-C port is a wasted effort.

The good news is that Garmin’s ShotView app is as simple to use, is as intuitive, as is the Xero unit itself. And ShotView has a feature for exporting a shot series to CSV, and thence out to your computer, via text, email, or AirDrop.

It’s quick and easy. And especially if you’re a shooter who habitually shoots only one or a couple of long sessions – all or most shots in one series, in other words – it’s almost a non-issue.

For those of us who do a lot of load development, though, who almost always come back with a fair number of different shot series, you’ll have to click through each series in turn, exporting them one at a time.

It’s not a big deal. But it shouldn’t be necessary.

Once you get the files exported and onto your computer, they’re fine. Here’s what the the Garmin file looks like, followed by the exact same shot series collected by the LabRadar.

And, finally, here is a size comparison. From left-to-right, the LabRadar, the Garmin Xero, the AndiScan (with its supplied case in front of it), and the FXAir (airguns only).

In sum, the new Garmin Xero Pro C1 is not perfect. But it’s close. What faults it has are really quite minor, niggles on an otherwise exemplary product. It’s what the LabRadar might have ended up looking like had Infinition continued to develop their product.

The AndiScan had the form factor, but failed on the rest of it.

I speak of both those chronographs in the past tense, because there’s no doubt in my mind that they are both done. I love them both. The LabRadar, in particular, has been my steadfast companion for what seems like an eon. But they are both done.

Now, like there once was, there is only one.