222Jim

Silver $$ Contributor

I’ve been hunting and shooting for over 50 years, but only started handloading for my .222 Remington and .22-250 Remington ten years ago. Before then, my children and career didn’t leave time for handloading. But, as children left home and I started thinking about retirement, I got into handloading. Why? Well, my varmint hunting partner for twenty years, who had handloaded for as long as I knew him, loaned me his bolt action .223 Remington and gifted me 20 of his handloads. I contributed a couple of boxes of premium factory ammunition that were loaded with the same bullet. A few hours of range time convinced me his handloads beat factory ammunition hands-down. Sadly, just after I bought my first press, he unexpectedly passed away. At that point I was on my own.

Ten years later, I’m at the point where me and my .22-250 Remington consistently achieve 20 shot groups at 100 meters with a Mean Radius of less than 0.20 inches, and less than 0.25 inches with my .222 Remington. Interestingly, most of my improvement was achieved over the past three years, and I attribute that to three things that I learned and I wished I knew when I started handloading.

You may have a different set of three, but in the interest of passing my experience along, I’m sharing my top three. There are a lot more lessons like full body versus neck resizing, tension and neck turning, bullet sorting, measuring your rifles maximum base-to-datum, or measuring your cartridge/bullet combination maximum base-to-ogive, or how to use, or abuse, handload design programs, and on and on. But here are my top three things that I wish I knew.

Oh, I inherited a sarcastic sense of humor from one of my grandfathers. The other contributed his self-depreciating sense of humor. So, if you’re expecting a pure unadulterated serious technical discussion, you’ll be disappointed………

1. There’s no magical or mystical method to develop precise handloads

Figuring this out sooner would have saved me time and money I wasted down the rabbit (node?) hole……

I learned that there isn’t a simple 10 or whatever number of shots magical or mystical method to find a precise handload. Simply put, statistics, which I happen to have a reasonable understanding of and did well in it in high school, is your friend. And your friend feeds on data.

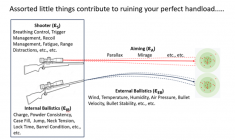

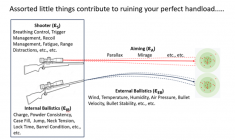

But in the forty years since high school, I forgot the basis of statistics, which is nothing’s perfect, including my shooting, and statistics can be used to measure and/or predict the consequences of those imperfections. Consequences that show up as a culmination of tiny and large errors in me, my shooting technique (as perfect as it may be), my rifle, my sight picture, my handload, and things that change the bullets flight path. All of that explains why I’ve had the bullseye perfectly lined up, and the bullet hits elsewhere else (yet usually on the target, thank God).

Eureka

I started to suspect something was amiss when I’d try to “find the node”. You know the “node”. That magical or mystical spot everyone talks about where the handload and rifle become one-with-the-universe. Where the velocity, vertical placement of the shots, and barrel vibrations are all in tune? The point at which velocity plateaus, as does vertical shot placement, and tiny bug-sized groups will emerge? Well, after pouring through online blogs, several reloading manuals, and lots of YouTube videos, I developed a load ladder of 10 loads in 0.30 grain increments for my .22-250 Remington. I drove 150 km (100 miles) to my range, set up my chronograph, fired those 10 shots, drove home, and with a Scotch in-hand, stared at my target. What was I staring at? Two velocity nodes (three if I squinted really hard), two vertical shot placement nodes, and the velocity and vertical shot placement nodes didn’t seem to come from the same powder charge. Must be the wind. So, back to the range with another ten shots and, it turns out, generate a new set of meaningless data. But I did enjoy the Scotch.

I’m a stubborn guy, and after four or five range trips and a bottle of Scotch, I was finally convinced I had that node nailed down. So back to the range to shoot 5 shots of that perfect load as proof of my handloading ability and shooting prowess. The results were pitiful. Maybe, if I was generous, a 3 inch or 4 inch group at 200 meters. It was a dead calm day, so the node obviously moved. I’d return to the range with a load 0.30 grains lighter a few weeks later, and then (yes, you guessed it) 0.30 grains heavier a few more weeks later. Each time I’d go home with my tail between my legs, and more often than not explain to my supportive spouse that this time the wind was gusty, or the guy next to me with the muzzle-braked 300 Winchester Magnum, was distracting me.

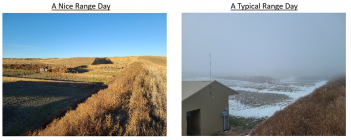

This went for several years and, mainly because when I got frustrated, I’d switch to the .222 Remington, or buy a new bullet or powder. Of course, another reason this went on for years is it’s seldom calm enough in the prairies to shoot 40 or 50 grain bullets at targets 200 meters away, so sometimes I’d have to wait two or three weeks, or months, between range sessions.

Then around Christmas three years ago, I was in my home office staring at targets while my barrel was soaking in copper cleaning solution. Bored, I stumbled across a YouTube video that talked about statistics for shooters. What intrigued me was the simple fact-based approach the presenters took to describe what was wrong with “finding the node” method, as well as the other methods people claimed you could use to find the perfect handload in 5 or 10 shots. Eureka.

Over the next few months, I poured through books, blogs, articles, and YouTube videos that focused on applying statistics to shooting. In the spring of 2020, I remember sitting back in my gunroom, staring at the assortment of bullets, powders, primers, and cases I’d tried, as well as the neck turning equipment and concentricity gauge, and wondered if it’s time for a new approach. One based on statistics. It did.

Over the past three years I learned a few simple lessons about applying statistics that took my groups from 3 or 4 inches in diameter at 200 meters, to less than 1-inch groups at 100 meters, and then to groups shot at 100 meters with a Mean Radius of less than 0.25 inches.

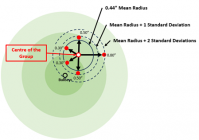

I learned I didn’t need to relearn statistics in detail

I’m not going to teach anyone how to calculate the Mean or Average (they are the same thing, but to confuse and scare students, they gave “average” a mean name), or even Standard Deviation. There are enough programs on calculators, built into Microsoft Excel, available as output on chronographs, and available in target analysis software and smartphone Apps to do that, and a lot more. I will explain though that Standard Deviation, which is very important to precision shooting, is simply a measure of how far the results are from the Mean, and if you have enough samples (more on that soon), and:

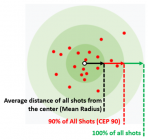

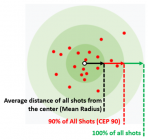

Having said that, I took things a little further. Why? Simply because most target analysis programs, including free online versions or programs you can buy, and even some smartphone Apps, will generate some form of statistical reports. An option I decide on was Circular Error Probability (CEP). CEP is simply a statistical prediction, based on the Mean Radius and Standard Deviation of the holes on the target, of how many shots will probably land within a given area. It was developed by the US Military for artillery, and now used in the shooting world. And frankly, if it’s good enough for US artillery, it’s good enough for me.

I happen to use the 90% predication (CEP 90). I’ve also leaned through experience that for me, CEP 90 is usually 1.8 times the Mean Radius. But that’s for me after firing hundreds of shots. The results? I’m now confident that 90% of my shots will land within 0.45 inch of my point of aim, i.e. 0.25 inch Mean Radius times 1.8 = 0.45 inches. Or, within a 0.9-inch diameter circle.

How many shots are enough?

There’s a concept that people over complicate known as “Sample Size versus Population”. Here’s my simpler explanation. I can get a precise Mean and Standard Deviation of how people will vote in my home province of Alberta if I got everyone to tell me their voting plans. But that’s not going to happen. So, what do political pollsters do? They ask a sample of people from the entire population how they plan to vote.

Sampling the population isn’t as precise, and hence reputable pollsters report it as “40% will vote for Fred, 9 times out of 10”, i.e., they have 90% Confidence that the 40% is correct. Shooting is no different, and the larger the sample is from the entire population, the more precise the Standard Deviation is.

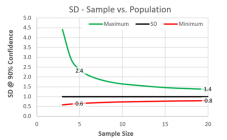

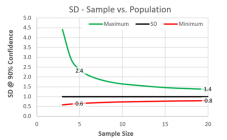

So how many shots are needed? To answer that question, I built this graph from online statistics resources. What it shows is the larger the sample, the closer and closer the sample Standard Deviation gets to representing the entire population. For example, let’s say I shoot 5 shots (.22-250 Remington with 40 grain bullets) and the Mean Radius is 0.25 inches and the Standard Deviation is 0.21 inches. But that 0.21 inches is the sample’s Standard Deviation. You can use this chart to estimate how small and big the Standard Deviation could be based on 5 shots out of an infinite number of shots. For the sample of 5 shots I fired, I can see that if I shot an infinite number of shots, the Standard Deviation would be between 0.6 and 2.4 times larger, i.e., 0.13 to 0.50 inches. But, if I shot 20 shots and the Standard Deviation was still 0.21 inches, then the Standard Deviation for an infinite number of shots would narrow down to between 0.8 to 1.4 times larger, i.e., 0.17 to 0.30 inches. That’s why I switched from 3 or 5 or 10 shot groups, to almost always 20 shot groups.

This same basic approach applies to bullet velocity, vertical dispersion of shots, etc.

2. Set a realistic goal

Sisyphus was punished by the god Zeus by forcing him to roll a boulder up a hill for eternity. Today, Zeus would punish Sisyphus by having him eternally improve his handloads…………

Gophers

Goals are personal and linked to what you’re shooting at. If I was a competitive target shooter, for example, a F-Class shooter, then I’d know exactly how big the target is and there is plenty of information on how well the top competitors do. So, I’d head to the range and score my targets!

I’m a varmint hunter and have a slightly different challenge. In my case, the smallest varmint I shoot is what us Albertan’s commonly refer to as “gophers”, but are in reality Richardson's Ground Squirrels. They weigh between ½ and 1 pound, and when they stand up, they are typically 7 inches tall and 2½ inches wide. This is prairie country, so shooting 200 – 300 meters is common, hence my goal was to be able to be able to consistently hit that 2½ inch wide target at 300 meters. That’s a reasonable goal too. Many varmint shooters routinely shoot gophers at that range, so if it’s good enough for them, it’s good enough for me.

So, most of the math is pretty simple. If it’s 2½ inches wide at 300 meters, then I need to think of it as 0.833 inches 100 meters away, i.e. 2½ inches divided by 3. But that’s the diameter, and most shooting statistics work on a radius, so divide that diameter by 2 and you get a radius of 0.417 inches, which we’ll round to 0.42 inches. Now what?

Well, I’ve seen friends and YouTube videos of shooters consistently hitting “gophers” at 200 – 300 meters, and I’ll define “consistently” as nine times out of ten. So, my goal is to be able to land 90% of my shots within 0.42 inches from what I’m aiming at. That’s why I’m using a Circular Error Probability of 90% (CEP 90) as my main measure of precision.

I’m now at that precision level with both of my rifles. Am I hitting 90% of the gophers at 300 meters? Yes and no. Yes, when I read the wind right; no when I don’t, or when the gopher is one of the lucky 10%. And, if I am going to try a new powder or bullet or primer, it’s got to be better than my current level of precision right off the bat. Otherwise, why waste the time and money trying to fine tune a new handload when the existing one meets my goal?

Load development at 100 or 200 meters?

For 7 years I did my handload development at 200 meters. Why? I’m chalking it up to ego. After all, I planned to shoot gophers out at 200 – 300 meters. As I transitioned from hunting and pecking for that node to a statistical approach, I did 100 and 200 meter tests. Why? No clear answer on which is better, or why, on the internet, blogs, YouTube, or in the manuals.

I had to fireform new brass, so I made 120 handloads and went to the range three times over a month. Each time, I’d fire 20 handloads at my then standard 200 meters, then 20 at 100 meters. At 100 meters the Mean radius and Standard Deviations for all three tests were statistically similar; at 200 meters they definitely were not. I have attributed that to the weather (I scaled targets to give me the same optical image for each test) and now do all my handload development at 100 meters.

But, one issue arose at 100 meters. Firing 20 shots at a target 100 meters away resulted in those shots eventually forming a single ragged-edged blob that was impossible to analyse. Just too many overlapping holes. But the target analyses program I use has the ability to combine multiple separate targets into one, and that’s what I use the center cross for; that’s where I combine all four 5 shot groups and get the 20 shot group analysis.

Shoot a control group

Finally, and I have no idea where I learned this, but it’s been invaluable. Shoot a control group.

What’s that? I now do a lot more research before trying out a new bullet/powder/primer combination. What I am trying to do is figure out what I think is going to be the more precise load. Then I clean my rifle, load 45 of those rounds, and wait until the range weather is as close to perfect as it can be. I fire five foulers/sighters, then slowly fire all 40 at two targets (20 on each target; 5 bullets at each of 4 “sub-targets”). I take my time and focus on shooting technique.

The result from this becomes my “control group”, and then I proceed to do my standard handload development around that control group’s design. After identifying the most precise handload through my load development steps, I load 45 of what I’ve decided is the most precise handloads, clean my rifle, and head to the range to fire those 45 rounds just like on “control group” day.

The big question then is “has my precision improved”? If it has, I smile to myself and this is now my handload for the rifle. If it hasn’t, then I’m forced to admit to myself that as the shooter, I need to work on my marksmanship skills………..

3. Buy the right equipment and components

Governments do not have a revenue problem; they have a spending problem. Am I any different?

In my first seven years I was a sucker for all sorts of magical components and equipment. I also upgraded my equipment a few times. Here’s three things I learned about buying the right equipment and components.

First, buy the best gear you can afford, and plan to leave it to your children. Show it to them. Write their names on it. That includes your powder scale, press, dies, calipers, an annealing system, and gauges. Only change them if you can demonstrate they are the cause of a problem big enough to explain to your children why you traded away their inheritance. Case in point. I replaced my press with a newer one because I couldn’t control my jump consistency to less than +/- 0.005 of an inch, and that makes it impossible to determine the most precise jump in 0.005 inch increments. After a year of trying and a lot of research, I replaced it and am now achieving jumps of +/- 0.001 of an inch. I’ll explain that to my son the next time he visits, from Toronto.

Second, stick to the tried-and-true powder, bullets, primers, and brass. Only switch one at a time, and only if you can’t achieve your goal. For me, I learned that my .222 Remington “likes” the classic load of IMR-4198 topped with 52 grain match varmint style bullets. In my .22-250 Remington it’s IMR-3031 topped by 40 grain match varmint bullets that works. Other combinations do to, but I achieved my goal with them, so other than occasionally tinkering around, why burn out my barrels? Plus, I’ve already invested too much money into different components!

Finally, as a varmint shooter, I regret buying a case concentricity gauge and primer pocket uniformer. I’m on the fence when it comes to my neck turning equipment until I do a statistically valid “turned versus not-turned” test. That’s something that’ll wait until I need to turn a new batch of cases…………

Ten years later, I’m at the point where me and my .22-250 Remington consistently achieve 20 shot groups at 100 meters with a Mean Radius of less than 0.20 inches, and less than 0.25 inches with my .222 Remington. Interestingly, most of my improvement was achieved over the past three years, and I attribute that to three things that I learned and I wished I knew when I started handloading.

You may have a different set of three, but in the interest of passing my experience along, I’m sharing my top three. There are a lot more lessons like full body versus neck resizing, tension and neck turning, bullet sorting, measuring your rifles maximum base-to-datum, or measuring your cartridge/bullet combination maximum base-to-ogive, or how to use, or abuse, handload design programs, and on and on. But here are my top three things that I wish I knew.

Oh, I inherited a sarcastic sense of humor from one of my grandfathers. The other contributed his self-depreciating sense of humor. So, if you’re expecting a pure unadulterated serious technical discussion, you’ll be disappointed………

1. There’s no magical or mystical method to develop precise handloads

Figuring this out sooner would have saved me time and money I wasted down the rabbit (node?) hole……

I learned that there isn’t a simple 10 or whatever number of shots magical or mystical method to find a precise handload. Simply put, statistics, which I happen to have a reasonable understanding of and did well in it in high school, is your friend. And your friend feeds on data.

But in the forty years since high school, I forgot the basis of statistics, which is nothing’s perfect, including my shooting, and statistics can be used to measure and/or predict the consequences of those imperfections. Consequences that show up as a culmination of tiny and large errors in me, my shooting technique (as perfect as it may be), my rifle, my sight picture, my handload, and things that change the bullets flight path. All of that explains why I’ve had the bullseye perfectly lined up, and the bullet hits elsewhere else (yet usually on the target, thank God).

Eureka

I started to suspect something was amiss when I’d try to “find the node”. You know the “node”. That magical or mystical spot everyone talks about where the handload and rifle become one-with-the-universe. Where the velocity, vertical placement of the shots, and barrel vibrations are all in tune? The point at which velocity plateaus, as does vertical shot placement, and tiny bug-sized groups will emerge? Well, after pouring through online blogs, several reloading manuals, and lots of YouTube videos, I developed a load ladder of 10 loads in 0.30 grain increments for my .22-250 Remington. I drove 150 km (100 miles) to my range, set up my chronograph, fired those 10 shots, drove home, and with a Scotch in-hand, stared at my target. What was I staring at? Two velocity nodes (three if I squinted really hard), two vertical shot placement nodes, and the velocity and vertical shot placement nodes didn’t seem to come from the same powder charge. Must be the wind. So, back to the range with another ten shots and, it turns out, generate a new set of meaningless data. But I did enjoy the Scotch.

I’m a stubborn guy, and after four or five range trips and a bottle of Scotch, I was finally convinced I had that node nailed down. So back to the range to shoot 5 shots of that perfect load as proof of my handloading ability and shooting prowess. The results were pitiful. Maybe, if I was generous, a 3 inch or 4 inch group at 200 meters. It was a dead calm day, so the node obviously moved. I’d return to the range with a load 0.30 grains lighter a few weeks later, and then (yes, you guessed it) 0.30 grains heavier a few more weeks later. Each time I’d go home with my tail between my legs, and more often than not explain to my supportive spouse that this time the wind was gusty, or the guy next to me with the muzzle-braked 300 Winchester Magnum, was distracting me.

This went for several years and, mainly because when I got frustrated, I’d switch to the .222 Remington, or buy a new bullet or powder. Of course, another reason this went on for years is it’s seldom calm enough in the prairies to shoot 40 or 50 grain bullets at targets 200 meters away, so sometimes I’d have to wait two or three weeks, or months, between range sessions.

Then around Christmas three years ago, I was in my home office staring at targets while my barrel was soaking in copper cleaning solution. Bored, I stumbled across a YouTube video that talked about statistics for shooters. What intrigued me was the simple fact-based approach the presenters took to describe what was wrong with “finding the node” method, as well as the other methods people claimed you could use to find the perfect handload in 5 or 10 shots. Eureka.

Over the next few months, I poured through books, blogs, articles, and YouTube videos that focused on applying statistics to shooting. In the spring of 2020, I remember sitting back in my gunroom, staring at the assortment of bullets, powders, primers, and cases I’d tried, as well as the neck turning equipment and concentricity gauge, and wondered if it’s time for a new approach. One based on statistics. It did.

Over the past three years I learned a few simple lessons about applying statistics that took my groups from 3 or 4 inches in diameter at 200 meters, to less than 1-inch groups at 100 meters, and then to groups shot at 100 meters with a Mean Radius of less than 0.25 inches.

I learned I didn’t need to relearn statistics in detail

I’m not going to teach anyone how to calculate the Mean or Average (they are the same thing, but to confuse and scare students, they gave “average” a mean name), or even Standard Deviation. There are enough programs on calculators, built into Microsoft Excel, available as output on chronographs, and available in target analysis software and smartphone Apps to do that, and a lot more. I will explain though that Standard Deviation, which is very important to precision shooting, is simply a measure of how far the results are from the Mean, and if you have enough samples (more on that soon), and:

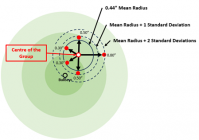

- 68% all of your results will be within +/- 1 Standard Deviation, and

- 95% within +/- 2 Standard Deviations.

- Mean Radius is 0.44 inches from the center of the group, and the

- Standard Deviation is 0.21 inches

Having said that, I took things a little further. Why? Simply because most target analysis programs, including free online versions or programs you can buy, and even some smartphone Apps, will generate some form of statistical reports. An option I decide on was Circular Error Probability (CEP). CEP is simply a statistical prediction, based on the Mean Radius and Standard Deviation of the holes on the target, of how many shots will probably land within a given area. It was developed by the US Military for artillery, and now used in the shooting world. And frankly, if it’s good enough for US artillery, it’s good enough for me.

I happen to use the 90% predication (CEP 90). I’ve also leaned through experience that for me, CEP 90 is usually 1.8 times the Mean Radius. But that’s for me after firing hundreds of shots. The results? I’m now confident that 90% of my shots will land within 0.45 inch of my point of aim, i.e. 0.25 inch Mean Radius times 1.8 = 0.45 inches. Or, within a 0.9-inch diameter circle.

How many shots are enough?

There’s a concept that people over complicate known as “Sample Size versus Population”. Here’s my simpler explanation. I can get a precise Mean and Standard Deviation of how people will vote in my home province of Alberta if I got everyone to tell me their voting plans. But that’s not going to happen. So, what do political pollsters do? They ask a sample of people from the entire population how they plan to vote.

Sampling the population isn’t as precise, and hence reputable pollsters report it as “40% will vote for Fred, 9 times out of 10”, i.e., they have 90% Confidence that the 40% is correct. Shooting is no different, and the larger the sample is from the entire population, the more precise the Standard Deviation is.

So how many shots are needed? To answer that question, I built this graph from online statistics resources. What it shows is the larger the sample, the closer and closer the sample Standard Deviation gets to representing the entire population. For example, let’s say I shoot 5 shots (.22-250 Remington with 40 grain bullets) and the Mean Radius is 0.25 inches and the Standard Deviation is 0.21 inches. But that 0.21 inches is the sample’s Standard Deviation. You can use this chart to estimate how small and big the Standard Deviation could be based on 5 shots out of an infinite number of shots. For the sample of 5 shots I fired, I can see that if I shot an infinite number of shots, the Standard Deviation would be between 0.6 and 2.4 times larger, i.e., 0.13 to 0.50 inches. But, if I shot 20 shots and the Standard Deviation was still 0.21 inches, then the Standard Deviation for an infinite number of shots would narrow down to between 0.8 to 1.4 times larger, i.e., 0.17 to 0.30 inches. That’s why I switched from 3 or 5 or 10 shot groups, to almost always 20 shot groups.

This same basic approach applies to bullet velocity, vertical dispersion of shots, etc.

2. Set a realistic goal

Sisyphus was punished by the god Zeus by forcing him to roll a boulder up a hill for eternity. Today, Zeus would punish Sisyphus by having him eternally improve his handloads…………

Gophers

Goals are personal and linked to what you’re shooting at. If I was a competitive target shooter, for example, a F-Class shooter, then I’d know exactly how big the target is and there is plenty of information on how well the top competitors do. So, I’d head to the range and score my targets!

I’m a varmint hunter and have a slightly different challenge. In my case, the smallest varmint I shoot is what us Albertan’s commonly refer to as “gophers”, but are in reality Richardson's Ground Squirrels. They weigh between ½ and 1 pound, and when they stand up, they are typically 7 inches tall and 2½ inches wide. This is prairie country, so shooting 200 – 300 meters is common, hence my goal was to be able to be able to consistently hit that 2½ inch wide target at 300 meters. That’s a reasonable goal too. Many varmint shooters routinely shoot gophers at that range, so if it’s good enough for them, it’s good enough for me.

So, most of the math is pretty simple. If it’s 2½ inches wide at 300 meters, then I need to think of it as 0.833 inches 100 meters away, i.e. 2½ inches divided by 3. But that’s the diameter, and most shooting statistics work on a radius, so divide that diameter by 2 and you get a radius of 0.417 inches, which we’ll round to 0.42 inches. Now what?

Well, I’ve seen friends and YouTube videos of shooters consistently hitting “gophers” at 200 – 300 meters, and I’ll define “consistently” as nine times out of ten. So, my goal is to be able to land 90% of my shots within 0.42 inches from what I’m aiming at. That’s why I’m using a Circular Error Probability of 90% (CEP 90) as my main measure of precision.

I’m now at that precision level with both of my rifles. Am I hitting 90% of the gophers at 300 meters? Yes and no. Yes, when I read the wind right; no when I don’t, or when the gopher is one of the lucky 10%. And, if I am going to try a new powder or bullet or primer, it’s got to be better than my current level of precision right off the bat. Otherwise, why waste the time and money trying to fine tune a new handload when the existing one meets my goal?

Load development at 100 or 200 meters?

For 7 years I did my handload development at 200 meters. Why? I’m chalking it up to ego. After all, I planned to shoot gophers out at 200 – 300 meters. As I transitioned from hunting and pecking for that node to a statistical approach, I did 100 and 200 meter tests. Why? No clear answer on which is better, or why, on the internet, blogs, YouTube, or in the manuals.

I had to fireform new brass, so I made 120 handloads and went to the range three times over a month. Each time, I’d fire 20 handloads at my then standard 200 meters, then 20 at 100 meters. At 100 meters the Mean radius and Standard Deviations for all three tests were statistically similar; at 200 meters they definitely were not. I have attributed that to the weather (I scaled targets to give me the same optical image for each test) and now do all my handload development at 100 meters.

But, one issue arose at 100 meters. Firing 20 shots at a target 100 meters away resulted in those shots eventually forming a single ragged-edged blob that was impossible to analyse. Just too many overlapping holes. But the target analyses program I use has the ability to combine multiple separate targets into one, and that’s what I use the center cross for; that’s where I combine all four 5 shot groups and get the 20 shot group analysis.

Shoot a control group

Finally, and I have no idea where I learned this, but it’s been invaluable. Shoot a control group.

What’s that? I now do a lot more research before trying out a new bullet/powder/primer combination. What I am trying to do is figure out what I think is going to be the more precise load. Then I clean my rifle, load 45 of those rounds, and wait until the range weather is as close to perfect as it can be. I fire five foulers/sighters, then slowly fire all 40 at two targets (20 on each target; 5 bullets at each of 4 “sub-targets”). I take my time and focus on shooting technique.

The result from this becomes my “control group”, and then I proceed to do my standard handload development around that control group’s design. After identifying the most precise handload through my load development steps, I load 45 of what I’ve decided is the most precise handloads, clean my rifle, and head to the range to fire those 45 rounds just like on “control group” day.

The big question then is “has my precision improved”? If it has, I smile to myself and this is now my handload for the rifle. If it hasn’t, then I’m forced to admit to myself that as the shooter, I need to work on my marksmanship skills………..

3. Buy the right equipment and components

Governments do not have a revenue problem; they have a spending problem. Am I any different?

In my first seven years I was a sucker for all sorts of magical components and equipment. I also upgraded my equipment a few times. Here’s three things I learned about buying the right equipment and components.

First, buy the best gear you can afford, and plan to leave it to your children. Show it to them. Write their names on it. That includes your powder scale, press, dies, calipers, an annealing system, and gauges. Only change them if you can demonstrate they are the cause of a problem big enough to explain to your children why you traded away their inheritance. Case in point. I replaced my press with a newer one because I couldn’t control my jump consistency to less than +/- 0.005 of an inch, and that makes it impossible to determine the most precise jump in 0.005 inch increments. After a year of trying and a lot of research, I replaced it and am now achieving jumps of +/- 0.001 of an inch. I’ll explain that to my son the next time he visits, from Toronto.

Second, stick to the tried-and-true powder, bullets, primers, and brass. Only switch one at a time, and only if you can’t achieve your goal. For me, I learned that my .222 Remington “likes” the classic load of IMR-4198 topped with 52 grain match varmint style bullets. In my .22-250 Remington it’s IMR-3031 topped by 40 grain match varmint bullets that works. Other combinations do to, but I achieved my goal with them, so other than occasionally tinkering around, why burn out my barrels? Plus, I’ve already invested too much money into different components!

Finally, as a varmint shooter, I regret buying a case concentricity gauge and primer pocket uniformer. I’m on the fence when it comes to my neck turning equipment until I do a statistically valid “turned versus not-turned” test. That’s something that’ll wait until I need to turn a new batch of cases…………